Former Hewlett Packard CEO Carly Fiorina described China as an imitator nation in her interview with Time in 2015:

I have been doing business in China for decades, and I will tell you that yeah, the Chinese can take a test, but what they can’t do is innovate. They are not terribly imaginative. They’re not entrepreneurial, they don’t innovate, that is why they are stealing our intellectual property.

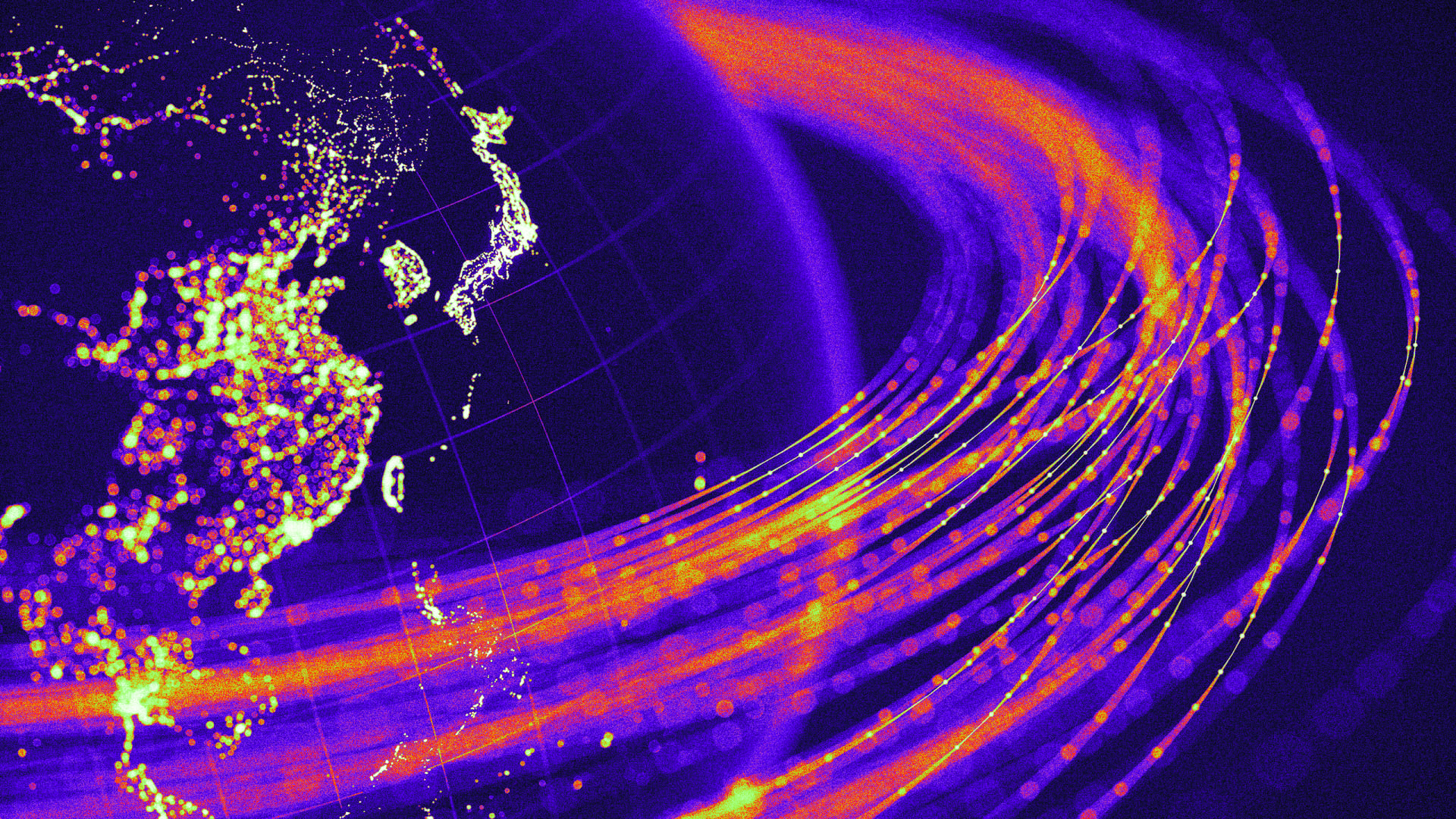

Fast forward to 2023, where little, yet everything, has changed. While the US Financial Times covers Chinese corporate espionage, China Daily touts its nation’s global innovation. The Financial Times reached out to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to learn how much of a nemesis China has become to the United States by stealing trade secrets, pirating software, and counterfeiting to the tune of $225–600 billion a year. China Daily counters this framing by arguing that China is a hub of global innovation. The Chinese media reminds the world that in 2018, China entered the global innovation index rankings of the top twenty most innovative countries in the world.

China’s list of achievements is impressive. It pioneered the world’s first quantum-enabled satellite, the world’s fastest supercomputer, the world’s largest and fastest radio telescope, the world’s first solar-powered expressway, the world’s largest floating solar-power plant, and the world’s thinnest keyboard. China Daily concludes confidently, “No matter how much the country’s creativity may differ from the West, China will lead the world as a global leader in science and technology by 2030.”

We are witnessing a creativity turn in the Global South as Indigenous innovators are looking at their people as creative assets, legitimate markets, and content partners to help build their data products and services. Yet the imitator label remains a sticky factor that translates to few creative industries in the West tapping into these global shifts.

Creative caste

Silicon Valley remains slow to recognize the geopolitical shifts in the creator economy. Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen explains how the West suffers from a “cultural captivity” syndrome, where a theory is born from the “accidental correlation between cultural prejudice and social observation.”9 Sen talks about the stickiness of how we imagine entire groups even when correlations die.

I call it the creative caste system, in which certain groups are believed to have an intrinsic ability to create original thought and content while others do not. Groups are marked by the nation and the context they happened to be born into. People’s gender, caste, race, and economic status play a part in how they are perceived on the creative spectrum, and the poverty stigma, in particular, runs deep. It is still a challenge for Big Tech to view low-income users as consumers, let alone as creators.

In 2022 I gave a keynote on the next billion creatives to UX researchers from the usual suspects like Meta, Google, Amazon, Spotify, and other North American tech firms. After my talk several e-commerce strategists approached me to explore the potential of live streaming for the Global South. This Western awakening is happening among consultancy firms such as McKinsey Digital, too. It released an article in 2021 titled “It’s Showtime! How Live Commerce Is Transforming the Shopping Experience.“ The gist of the article is to convince Western businesses to blend entertainment with purchasing by using live streaming for e-commerce. While Western tech is waking up to this supposedly novel opportunity, in China, this is old news. China’s creator economy is now a mature ecosystem with a market size of $20 billion in 2021. China is already home to the world’s biggest live-commerce player, Taobao, with a market share of 35 percent. By 2020, almost 30 percent of Chinese internet users shopped via live streaming. Chinese apps realized years ago that content creators need to be able to monetize their talents and fanbases, or they would look elsewhere to set up home. US tech still grapples with interoperability and content monetization.