When Sabine Dulac, a marketing manager for a French luxury goods company, moved from Paris to London, she was looking forward to working in a more practical and efficient environment. Her new boss in the London office was American, and she walked out of her first performance review with him feeling confident. According to Sabine, it was the best review of her career.

Her boss didn’t see it that way. Instead, he felt Sabine’s performance was sub-par and she needed to make a few improvements in order to keep working on his team. In this case, cultural differences led to both sides misinterpreting the feedback–and neither were aware of it.

Different Styles And Subtexts

As technology helps the modern workplace become ever more global, people from different backgrounds find themselves working more closely together than ever before. Even where there isn’t a language barrier, there can still be a cultural one.

Those can be hard to detect, in part because it’s hard to quantify the differences in the ways people communicate without generalizing: Is X behavior a cultural trait, or just a matter of Y individual’s personality? Still, social scientists and management experts have identified some common features. For instance, Americans are typically perceived around the workplace to be direct and transparent, but when it comes to giving feedback, this stereotype falls flat. Explicit and clear in many other ways, Americans tend to be so overwhelmingly positive while giving feedback that people from other countries often struggle to figure out when they’re being chewed out and when they’re being praised.

Managers in different parts of the world are conditioned to give feedback in drastically different ways. In general, the Thai manager learns never to criticize a colleague openly or in front of others, while the Dutch manager learns to be as honest as possible and give the message straight. The French are generally taught to criticize passionately and provide positive feedback sparingly, while Americans commonly learn to give three positives with every negative and call people out for doing things right (which may be downright confounding to many raised in other cultures).

“Upgraders” And “Downgraders”

One way to begin gauging how a culture handles negative feedback is by listening to the types of words people use. People from cultures that tend to be more direct with criticism typically use what linguists call “upgraders,” words preceding or following negative feedback that make it sound stronger, such as “absolutely,” “totally,” or “strongly.” For instance: “This is absolutely inappropriate,” or “That is totally unacceptable.”

By contrast, other cultures are less direct, relying more heavily on “downgraders” while dispensing criticism in order to soften the blow. Those include “kind of,” “sort of,” “a little,” “a bit,” “maybe,” and “slightly.” Sometimes downgraders come as deliberate understatements like, “We are not quite there yet,” when what you really mean is, “This is nowhere close to complete.”

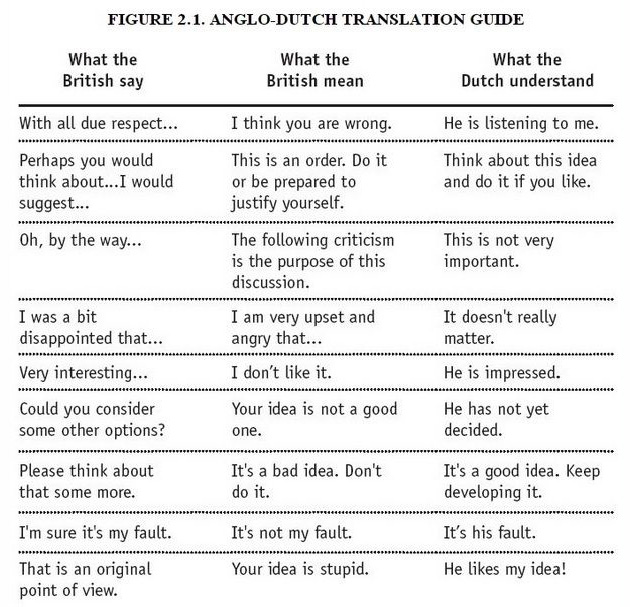

This “Anglo-Dutch Translation Guide,” which has been anonymously circulating in various versions on the Internet, provides an illustration:

For Marcus Klopfer, a German client I interviewed, this guide was no laughing matter. He explained how a misunderstanding with his British boss almost cost him his job:

In Germany, we typically use strong words when complaining or criticizing in order to make sure the message registers clearly and honestly. Of course, we assume others will do the same. My British boss, during a one-on-one, “suggested that I think about” doing something differently. So I took his suggestion: I thought about it, and decided not to do it. Little did I know that his phrase was supposed to be interpreted as “change your behavior right away, or else.” And I can tell you I was pretty surprised when my boss called me into his office to chew me out for insubordination!

For Marcus, the experience was a vivid lesson in distinguishing between upgraders and downgraders, and it’s helped him navigate the finer points of the feedback experience across cultures:

I learned to ignore all of the soft words surrounding the message when listening to my British teammates. Of course, the other lesson was to consider how my British staff might interpret my messages, which I had been delivering as “purely” as possible with no softeners whatsoever. I realize now that when I give feedback in my German way, I may actually use words that make the message sound as strong as possible without thinking much about it. I’ve been surrounded by this “pure” negative feedback since I was a child.

All this is quite interesting, funny, and sometimes downright painful when you’re leading a global team. You might sit down for a morning of annual performance reviews, and as you Skype with your employees from different backgrounds, your words might be silently magnified or minimized in each of their ears according to the cultures they’ve grown up in.

Accounting for that possibility starts with simply being aware of it. You have to work to understand how your own feedback tendencies are perceived in other cultures. You have to recognize when you’re using upgraders and downgraders, and when your international colleagues are using them. Once you’ve begun picking up on that, you can experiment a little to adjust them to the context until you get the message right.

As Marcus told me:

Now that I better understand these cultural tendencies, I make a concerted effort to soften the message when working with cultures less direct than my own. I start by sprinkling the ground with a few light, positive comments and words of appreciation. Then I ease into the feedback with “a few small suggestions.” As I’m giving the feedback, I add words like “minor” or “possibly.” Then I wrap up by stating that “this is just my opinion, for whatever it is worth,” and “you can take it or leave it.”

From Klopfer’s point of view–and probably from many fellow Germans’–this elaborate dance is quite humorous. “We’d be much more comfortable just stating, Das war absolut unverschämt“–“That was absolutely shameless”–he says. “But it certainly gets my desired results!”

Sometimes, the most effective cross-cultural communication isn’t always the most direct.

This article is adapted from The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business by Erin Meyer, a professor at INSEAD and an expert in cross-cultural management. Follow her on Twitter at @ErinMeyerINSEAD.