In 2007, even the most die-hard Britney Spears fans wondered whether the reigning Princess of Pop still wanted the title anointed upon her at age 16. After all, the most disturbing images of that year cling stubbornly to the mind, from her public meltdown against paparazzi to the infamous VMA performance that might have ended her career. Of course, she immediately but narrowly rebounded as only she could: with Blackout, an album many regard as her best.

Yet in the years that followed, Spears failed to ride that momentum, producing a handful of moderate hits from albums that never quite hit the mark. By the time 2013’s critically panned Britney Jean arrived, she had mostly overcome those frightening images from her past, offering instead the picture of a healthy 34-year-old who lounges poolside with her family and takes her sons out for Sunday morning hikes. She had successfully made the case for Britney Spears, the mom and Instagram persona—but not Britney Spears, the pop star.

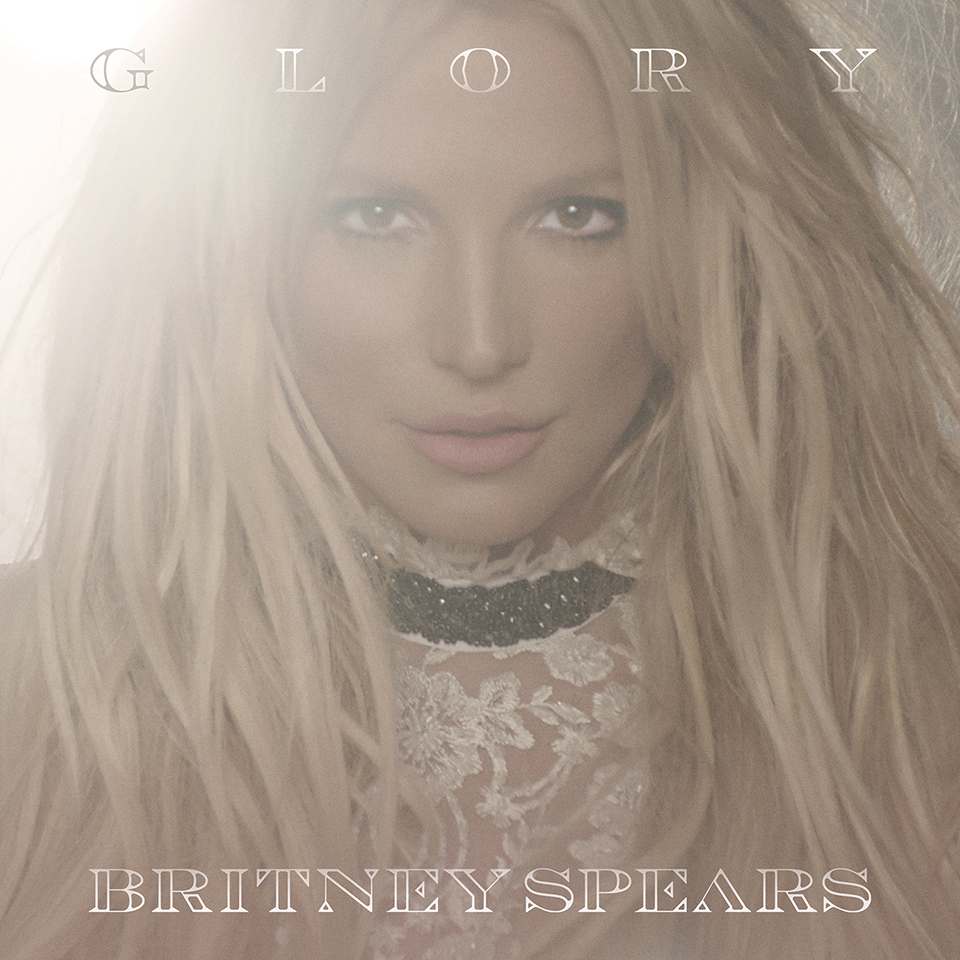

That may change now with Glory, her ninth studio album, which just gave Spears’s side gig as the world’s biggest pop star a jolt of much-needed goodwill beyond the enduring nostalgia that’s arguably kept her afloat over much of the last decade. Hailed as a “masterpiece” and her “most adventurous album in a decade,” Glory has seemingly accomplished what the three records before it had hoped for: the rehabilitation of the nearly 20-year-old Britney Spears brand.

Much of the credit should go to Karen Kwak, the industry veteran who served as executive producer for Glory. Hired last summer after the widely derided single “Pretty Girls”—“That’s kind of an unofficial disclaimer, huh?” she says—she arrived at the precise moment when Spears seemed destined to take the Madonna route of latching onto younger, hotter artists (“Pretty Girls” featured Iggy Azalea, whose fading public persona did little to boost the song’s reception) and churning out derivative forms of modern pop music for a shot at relevancy. Kwak seemed charged with cleaning up that mess.

“It was a definite pinch-me moment,” she says of coming aboard Spears’s team. Yet more than that, she faced a unique challenge of branding in pop music—not just bouncing back from a poorly received single, but also pivoting from a culmination of issues including a breakdown, legal problems, and the simple question of whether or not Spears longed to remain a celebrity. A court-approved conservatorship, which puts her father and a lawyer in charge of key personal and financial decisions, may very well be what keeps Spears—who would rather be remembered as a mother than an artist—in the recording studio and onstage for her popular Las Vegas show.

Still, in a time when pop stars such as Taylor Swift conduct damage control publicly on Instagram, Kwak had the task of putting together an album that would do the same for Spears.

The key to reinventing Britney Spears for 2016, Kwak says, was to not reinvent at all. At first, she wanted to think of Glory as a standalone product, but soon sensed that was impossible. Recapturing the playfulness absent on Spears’s past few records would mean getting back to basics. “We took references from Blackout, but that wasn’t intentional,” she says. “What we did use was the Britney I knew from the outside, before we worked together. The Britney that was always taking chances, always changing, and always doing something new.”

That being said, Kwak kept the album forward facing. “We didn’t talk about the past,” she says, hesitating to comment on the extent to which Britney Jean—considered the blankest, least Britney Spears-sounding album to date—affected Glory‘s creative process. “I can’t speak for the previous albums. But here, she seemed like she was present and actually having fun.”

That much is apparent over the course of 17 tracks, whether on the lead single and spin class fave “Make Me . . .” or the Top 40-ready “Do You Wanna Come Over?” More than any recent album, Glory actually sounds like Britney Spears, putting her front and center in a way that she hasn’t been in over a decade. Where she was once processed and robotic beyond recognition, she’s reassumed a sense of self and control over her music.

Spears’s involvement and “deep commitment” to the project yielded two of the album’s most experimental tracks: the warbling “Private Show” and the sung-entirely-in-French “Coupure Électrique.” Kwak says the apparent randomness of the former is a product of Spears’s diverse music tastes, while the latter came about when she, apropos of nothing, decided, “I want to sing a French song.” Yet however bizarre the two may seem, they remain quintessentially Britney; “Private Show” showcases all the signature vocal tics lauded and critiqued over the years, and “Coupure Électrique” translates, winkingly, to “blackout.”

The creative output seems a direct result of Kwak giving Spears room to play and be herself, while still keeping her in line with the demands of a major label release. “I was a filter for her, dealing with all the writers and producers who wanted to work with her,” she says. “My job was creating a process committed to good music and making sure she enjoyed doing what she loves.” That, and getting Spears out of the studio early enough daily that she could pick her boys up from school.

Though she says they never set out to create a number one song, Kwak—who has also served as artist and repertoire (A&R) for Rihanna, Justin Bieber, and Frank Ocean—has a keen enough sense of hit-making that she produced a Britney Spears album that wouldn’t sound out of place in 2003 or 2016. She takes particular issue with the critique that Glory isn’t personal enough, at least not in the way of “Everytime” or “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman.” “This is a reflection of where she is after 20 years of everything being scrutinized,” she says. “If she’s in a happy place, in a good place, then I think that’s okay.”

Certainly Glory shows Spears as she is today, every bit as fun and random as her Instagram account, which mixes selfies and behind-the-scenes pictures with inspirational quotes and shoehorned promotional material. If Circus, Femme Fatale, and Britney Jean raised any doubts about her remaining interest in pop stardom, then Glory temporarily puts the breaks on those questions.

In the meantime, Kwak has helped Spears backpedal from the possibly irreversible point where she might have kept putting out uninspired music until her fans—or perhaps her conservators—finally stopped asking that of her. Glory, at least for now, gives her the chance to live up to those heights.

“If Britney is calling this album her baby,” Kwak says, “then I’m kind of like the midwife.”

The application deadline for Fast Company’s World Changing Ideas Awards is Friday, December 6, at 11:59 p.m. PT. Apply today.