During a series of record-breaking heat waves in California in August—when Death Valley reached nearly 130 degrees Fahrenheit, believed to be the hottest temperature ever recorded on the planet, and hundreds of wildfires spread throughout the state—the electric grid strained under the pressure of running millions of air conditioners. In some areas, the state’s electric utility instituted rolling blackouts. But as demand was peaking, one startup tested a potential solution: a “virtual power plant” that could help keep the lights on.

The company, called OhmConnect, pays customers to save energy at key moments, helping to avoid blackouts. Today, Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners, a spinoff of Alphabet’s Sidewalk Labs that launched earlier this year, announced that it was committing $100 million to OhmConnect to scale its solution up. The funding will build North America’s largest virtual power plant, called Resi-Station.

The traditional grid, with a basic hub-and-spoke model that sends power from large centralized power plants to customers, is changing. If houses have solar panels on the roof and batteries to store the power, for example, they can be coordinated to send energy back to the grid when it’s needed. One of the first virtual power plants in the U.S. will be a neighborhood under construction in Arizona where every home is equipped with solar panels and a battery. Electric cars plugged into homes can also become part of a network, sending back power to the grid when the it’s needed. The model that OhmConnect uses, reducing customer demand, is another part of the new distributed system. “What you’re trying to do is to aggregate and orchestrate those distributed resources in a way that you can then transact in the energy market, similar to the way that a natural gas power plant does,” says Winer.

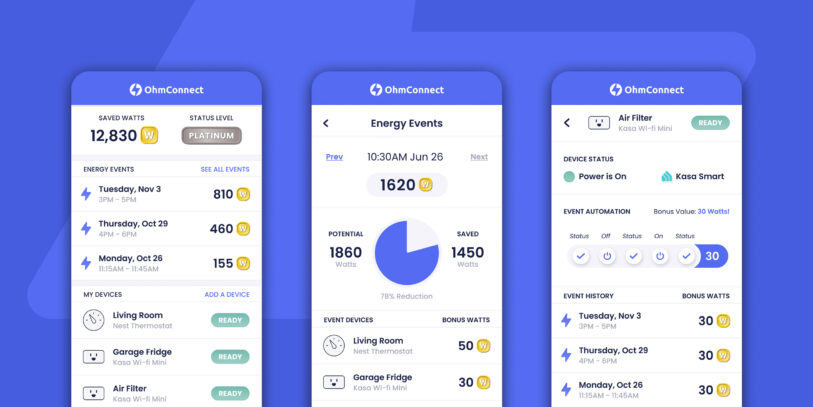

When demand surges, utilities typically have to turn on a “peaker” power plant running on coal or natural gas (the plants are disproportionately located in low-income neighborhoods of color that have to then deal with the air pollution as the fossil fuels burn). Now, instead of running fossil plants—or having to build more—it’s possible to turn to the distributed system and incentivize reduced use. When demand peaked in California in August, OhmConnect paid its customers to reduce nearly a gigawatt-hour of energy usage, or roughly the equivalent of taking more than 600,000 homes off the grid for an hour. The system is simple: when customers sign up for the free service, the company will occasionally send a text asking them to save energy for, say, an hour, and then gives a credit based on what they likely would have used otherwise. Customers can also opt-in to have their smart devices automatically reduce usage through the program. Utilities then pay OhmConnect for the service.

With the new investment, the partners plan to spend $80 million to offer Californians subsidized smart home devices, such as Nest thermostats, when they enroll in the program. Then the app starts sending alerts. It might say, “‘Hey, thanks for installing the thermostat we sent you, that’s great,'” Winer says. “‘If you’re willing to move your temperature by two degrees, on Wednesday in your home, we’re able to pay X dollars.'” While utilities are also beginning to send similar alerts directly themselves, the startup takes a gamified approach that it says can be more effective at increasing participation. Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners also invested $20 million directly in the startup. The funding is expected to bring on enough new homes to scale up the virtual power plant to 550 megawatts, making it the largest in North America. (For comparison, that’s the same capacity as the Boardman Coal Plant in Oregon, which closed in October, but previously was the largest single source of emissions in that state.)

Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners is focused first on California because the state has policies that support this type of system, but other states will follow. “We’re already seeing that the utilities in Texas and in New York, who have been studying the California program, are in the process of putting their own policies in place,” he says. “They’re not quite in place yet. But as soon as they are we’ll look at expanding to other markets as well.”