COVID-19 has changed the way we dress: Stuck at home, we’ve ditched suits and party frocks for sweatpants and nap dresses. But this isn’t the first time in history that a major world event has altered fashion. World War I also led to seismic shifts: Women ditched constricting corsets for bras, comfy jersey fabric was all the rage, and pockets were in mass-produced women’s garments for the first time.

These are among the insights from a new exhibit called Silk and Steel: French Fashion, Women, and WWI, currently on display at the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri, and previously shown at the Bard Graduate Center. Developed by fashion historians Maude Bass-Krueger and Sophie Kurkdjian, the show reveals how moments of global crisis can transform our relationship to clothing. It offers a glimpse into how the current pandemic may influence the way we dress going forward.

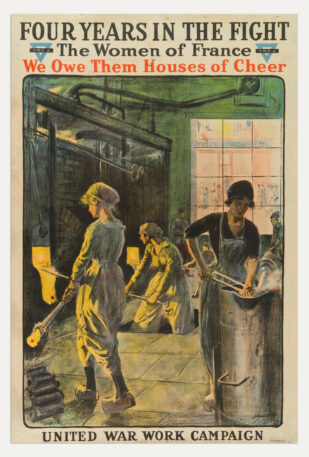

Crises change work

In many ways, the last century of Western fashion has been a story of casualization. Before WWI, upper-class French women–who were the arbiters of style–would change their outfits as often as five times a day. There were specific, elaborate outfits for different occasions, such as morning gowns, tea dresses, and ensembles for the opera. When the war exploded across Europe, wealthy French women ditched these impractical outfits and began to wear tailored suits. The look had been imported from England and had been popular among working-class women for decades, but after the war began, it became the default for women of all social classes. This trend echoed around the world.

This was also the start of women embracing aspects of menswear: Later, in World War II, more women would wear trousers, which paved the way for modern fashion. “Some [women’s] suits imitated soldiers’ uniforms,” says Lora Vogt, curator of education at the WWI Museum. “Many of the women enlivened their outfits with jewelry or white lace collars in order to enhance their femininity and counter criticism about how they subverted gender roles through their wartime work.”

The death of the corset, the birth of the pocket

This shift toward more casual clothing during WWI led to several major innovations in women’s dress. For one thing, many women ditched the restrictive corset for the bra. The concept of the bra had been circulating before the war started; in the U.S., the first patent was received by debutante Mary Phelps Jacobs in 1914, three years before the country officially entered WWI. But it was during the war that the garment was widely adopted. “There was a global shift to garments that allowed greater movement,” says Vogt. “War quickened the process of the acceptance of what may have earlier been seen as scandalous or too progressive.”

Opportunities to Innovate

During WWI, some male tailors and dressmakers were drafted, forcing them to close their operations. Other fashion houses pivoted to helping the war effort create bandages, shirts, and socks for soldiers. It’s similar to the way that many brands and designers began making masks at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The war also gave one of the world’s most famous designers her start. Gabriel Chanel was a hatmaker who rose to prominence during WWI for cleverly using jersey material to make everyday outfits. Vogt says jersey has existed since the Middle Ages, but it was used to make underwear and sportswear. During the war, wool and silk were used for soldiers’ uniforms, but silk jersey was widely available, so Chanel used it to create practical outfits that became iconic: simple skirts and jersey coats with large pockets and belts. “Chanel brought this unassuming fabric into the realm of everyday fashion,” says Vogt.

The fashion shifts during WWI bear some similarities to what we’re seeing now. The pandemic has also pummeled the fashion industry, disrupting supply chains and causing some businesses to go bankrupt. But one lesson from the past is that innovative designers that adapt to the moment have an opportunity to make their mark on the world.

And the pandemic, like the war, has changed our lifestyles. Many of us are working from home, which forces us to rethink what we wear during the day. There are already signs that remote work will outlast the pandemic. So are sweatpants and nap dresses here to stay? If history is a guide, the answer seems to be “yes.”